I had a conversation the other day with my colleague Kevin. He thinks that the future will be separated by those who can do what they want and those who can’t.

I like discussions like this because I tend to create binary views, so debating this versus that is fun.

I think a lot of what we consider segmenting factors in society—race, class, education, health, etc.—are actually subsets of this bigger idea that humans either do what they want or they don’t.

In the past, if you were black in America, life was hard(er). But mostly, it was hard because you couldn’t do what you want—it’s just that it was to a degree we all hope to never experience. Same could be said for religious separations, like Jews during World War 2. Or by sex, with women being relegated unfairly for eons. And so on. These were all extremely broad, instantly limiting factors.

The good news is that all these past barriers appear to be dissolving every day based on the hard work of many people. I think we can all say that globally race, sex, ethnicity, and even class are becoming less of a hurdle towards allowing someone to, in effect, do what they want, relatively speaking. That goes without saying that obviously the ills of old still exist, and en masse. But progress can be found across the board.

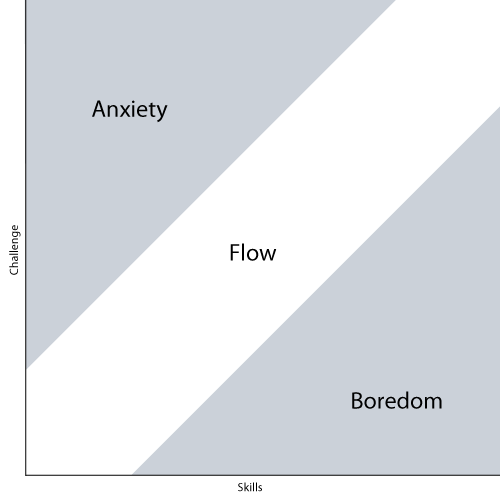

Choosing what you want to do then being able to do it is still an elusive endeavor, however, and I don’t think humans will ever fix it at scale. So, then we have to ask ourselves what will be the limiting factor in the future, especially if the traits of old are going away? This was the juicy heart of the conversation, and the one worth most thought.

Kevin and I agreed that it comes down to perceived lifestyle versus actual lifestyle, which in turn is essentially a macrobrew of your race, sex, ethnicity, education, environment, class, and everything else. Life situations and decisions, whether forced or chosen, basically dictate your ability to do what you want, and, when put up against what you desire to be doing at that time, can have a satisfying or horrifying outcome. (I guess or somewhere in between. Darn binary views!)

The ironic part is a lot of times “doing what we want” and its outcome dictates what you can choose to do in the future.

For example, let’s say a couple decides to have a child at age 25 compared to 35. Children are really expensive. The last anecdotal figure I heard is a child will cost you well over a million dollars in its 18-year reign, and the ROI is predominantly personal happiness provided you nurture a healthy relationship. Money isn’t everything, though—figuratively and literally. A child also consumes most of your time when they are young. Many hobbies and ambitions are sacrificed to care for your offspring. (At times I think we as children fail to realize this until we are actually parents, then have such appreciation towards our own forever.)

Many sociologists believe teen pregnancy can be the biggest limiting factor keeping poor classes poor. More often than not, the expense and attention the child demands coupled with a potentially lackluster support system prevent the teen mother from pursuing an education that would be the catalyst out of one class to another, preventing her from “doing what she wants”.

Here are some other examples that have the same affect:

- Taking a job in a specific location

- Committing a felony

- Not getting an education beyond high school

- Accumulating massive debt (like by getting an education beyond high school)

- Picking a specific, limiting career

- Getting married (although great, it does change your life scope)

- Leading an unhealthy life (diet, drugs, etc.)

- Or simply having personal beliefs or traits that make you fearful to do the things you want

And these are just some examples of life choices that we make which change our scope of future decisions, thus creating impenetrable laws blocking us from what we want to do.

Now lets say a 20-something decides to phone-in the decade. Ten years of escalating vices all in the name of never “growing up”. What might be the motif of every Judd Apatow movie script is actually an emerging lifestyle among my generation. What used to be 17 is the new 24. Fear of being “tied down” to anything serious like jobs, careers, relationships, apartments, beliefs, hobbies, and kids—in aggregate, “responsibility”—is basically an evolutionary trait enabled by an unintentional alchemy since the 1980s.

It’s a well known fact that parents spend their entire life trying to make their kids’ lives better than theirs. We reached a tipping point in the 80s, which aggressively excelled in the 20 years following, that turned the lives of Generation X and, more specifically, Mellennials into a cake walk. Basically, Baby Boomers were both wonderful and shitty parents. The spoils we had as children allowed us to continue to not face hardship until we reached our 30s.

And then college happened. A bachelors became the new high school diploma. Everyone needed to go to college. The massive increase in enrollment was part byproduct of our parents wanting to do only what’s best for us (and the shear number of them who could now do that), and part social Darwinism (good luck getting a job like your parents if you don’t have a degree). But most importantly, the fact that the majority of my generation went to college meant that we had another four years—at least—without responsibility. We were free to explore ourselves, the world, possibilities. And frankly, we kind of like it. College was the biggest enabler to allowing us to “do what we want”.

Millions of 20-somethings are now stuck, though, as the arms race in this luxury warfare continue to escalate. They are looking at the choices and non-choices during this new century as the keys to being able to do what they want, or force to do what they don’t.